Supported by

Exhibition Review

70 Years on, Magic Concocted in Exile

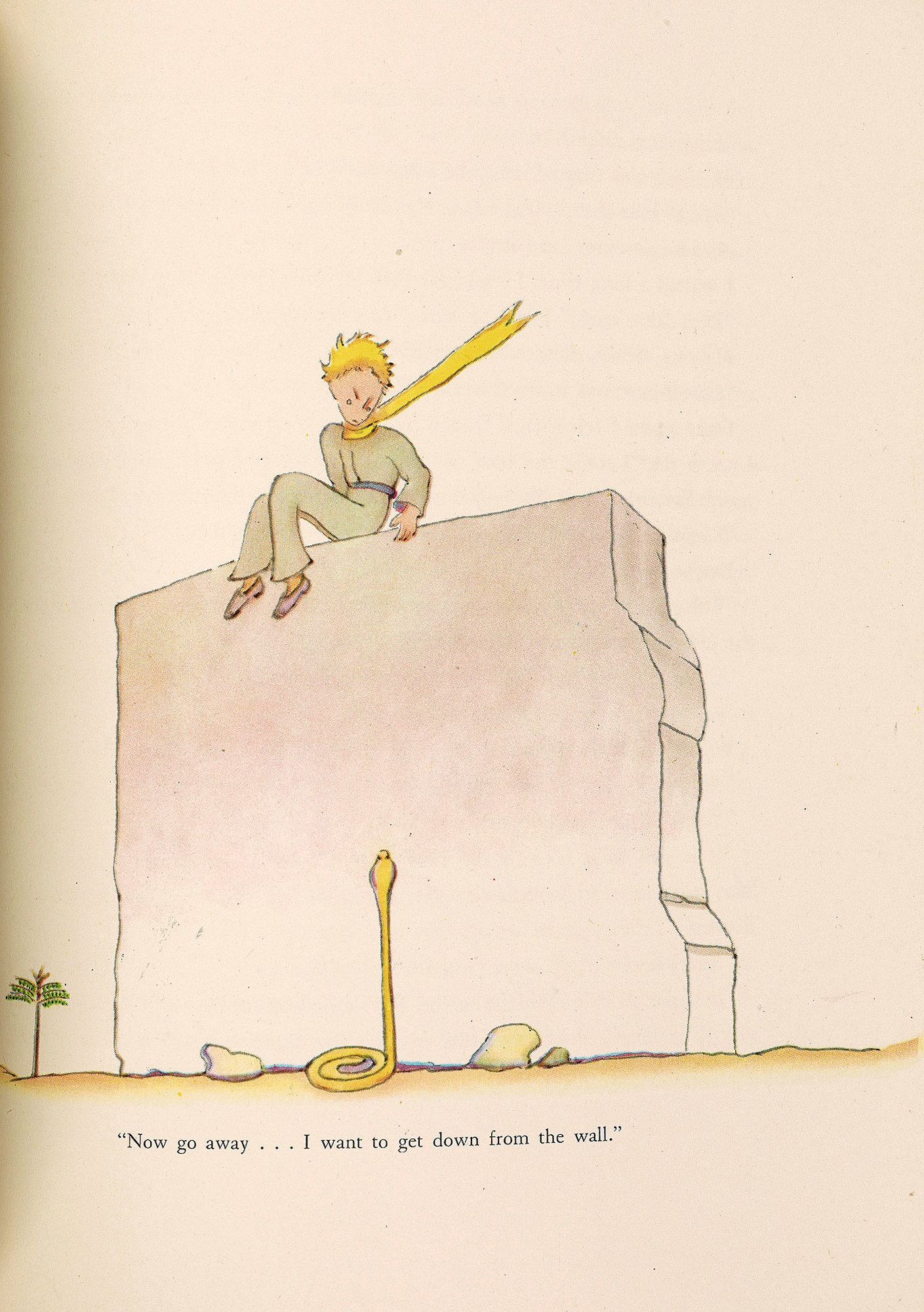

If you are one of those people who, on looking up at the heavens, wonder whether a sheep on a particular asteroid has eaten a certain flower, or if you already know the fox’s solemn secret — “Anything essential is invisible to the eyes” — then no new incentives will be required to visit the exhibition that opens Friday at the Morgan Library & Museum, “The Little Prince: A New York Story.” You are already an initiate.

But if you are one of those who have never ceased to love children’s literature yet find notions of a laughing star, a vain flower and an innocently wise yellow-scarfed prince in the Sahara a bit precious and overwrought — if, that is, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s 1943 mega-seller classic never inspired your own cultic devotion — then the exhibition should be seen anyway.

Of course, it helps to approach “The Little Prince” with at least some curiosity about how it ended up inspiring such allegiance. It has been translated from the original French into some 250 languages and dialects and has been selling over 1.8 million copies a year; it has inspired films, sequels, a Japanese museum, and works of opera and ballet. The exhibition even shows us a screenplay that Orson Welles wanted to use to film the book in 1943 with special effects by Walt Disney — until it became clear how impossible such a collaboration would be. (Welles claimed that Disney stormed out snapping, “There is not room on this lot for two geniuses.”)

It is intriguing, too, that Saint-Exupéry, an aviator of French aristocratic heritage in self-imposed exile from the Nazi-aligned Pétain government, would choose to follow his best-selling 1942 account of a reconnaissance flight he piloted during the German invasion (“Flight to Arras”) with a tale lacking any overt sign of battle, one that “even grown-ups” (as he might have put it) could embrace.

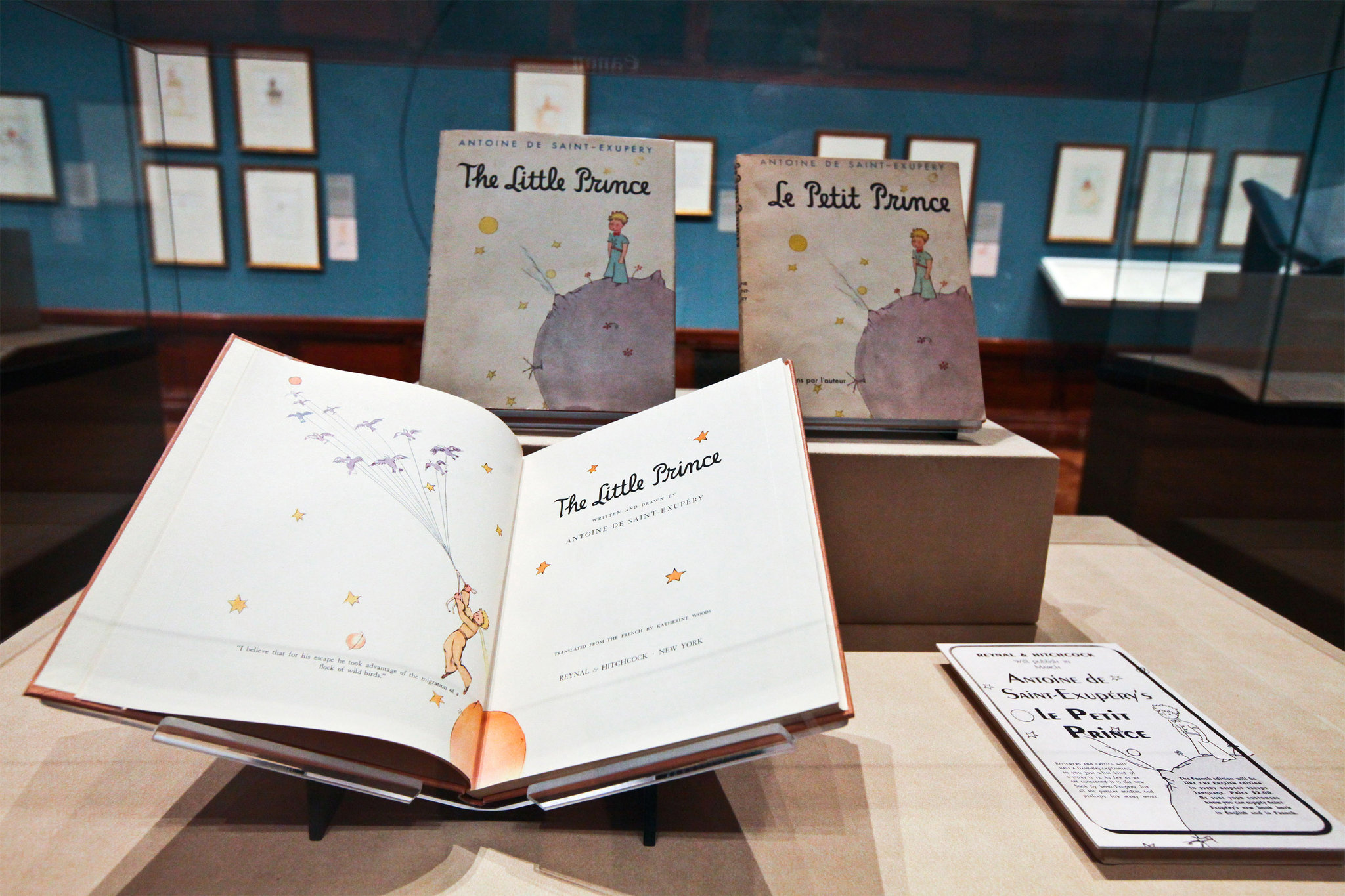

At the Morgan, though, the book is approached from another direction. Christine Nelson, curator of literary and historical manuscripts, has focused this exhibition not just on the book, but on its origins as well. Despite its foreign language and exotic locales (Saint-Exupéry never learned English), it was closely connected to New York. It is here that he had come to live with his wife on the last day of 1940. It is here that a French-speaking friend, Elizabeth Reynal, suggested that he turn the wan, waifish figure she saw in his doodles into the protagonist of a children’s book. (Several drawings of that proto-prince in the exhibition were gifts to her.)

Reynal and another friend, Peggy Hitchcock, feted and fed Saint-Exupéry and found him his apartment on Central Park South. Their husbands were partners in Reynal & Hitchcock, the firm that published “The Little Prince” in 1943 in French and English. (The book wasn’t published in France until 1946.)

The Morgan is also displaying Saint-Exupéry’s silver identity bracelet, bearing the address of those New York publishers — a bracelet found snagged in a fishing net off the coast of Marseille in 1998; until then, there had been no sign of the long-missing aviator, who had rejoined his squadron days after his book was published, only to go down in an Allied reconnaissance flight in July 1944; the plane’s wreckage was finally found 60 years later.

From the years when Saint-Exupéry was writing “Le Petit Prince,” we see a picture of the extraordinary Victorian mansion on the North Shore of Long Island that had been rented by his wife, Consuelo. (Their relationship was combative, rife with infidelities and provocations.) “I wanted a hut,” Saint-Exupéry complained of the summer house, “and it’s the Palace of Versailles.” But it was there that a visitor posed for a sketch that we see, serving as a model for a little prince in despair.

There are images of other relevant New York locations (which in 1989 inspired a Saint-Exupéry New York walking tour), including a friend’s salon (now the site of the restaurant La Grenouille), a home on Beekman Place and the apartment of another of Saint-Exupéry’s devoted muses, Silvia Hamilton.

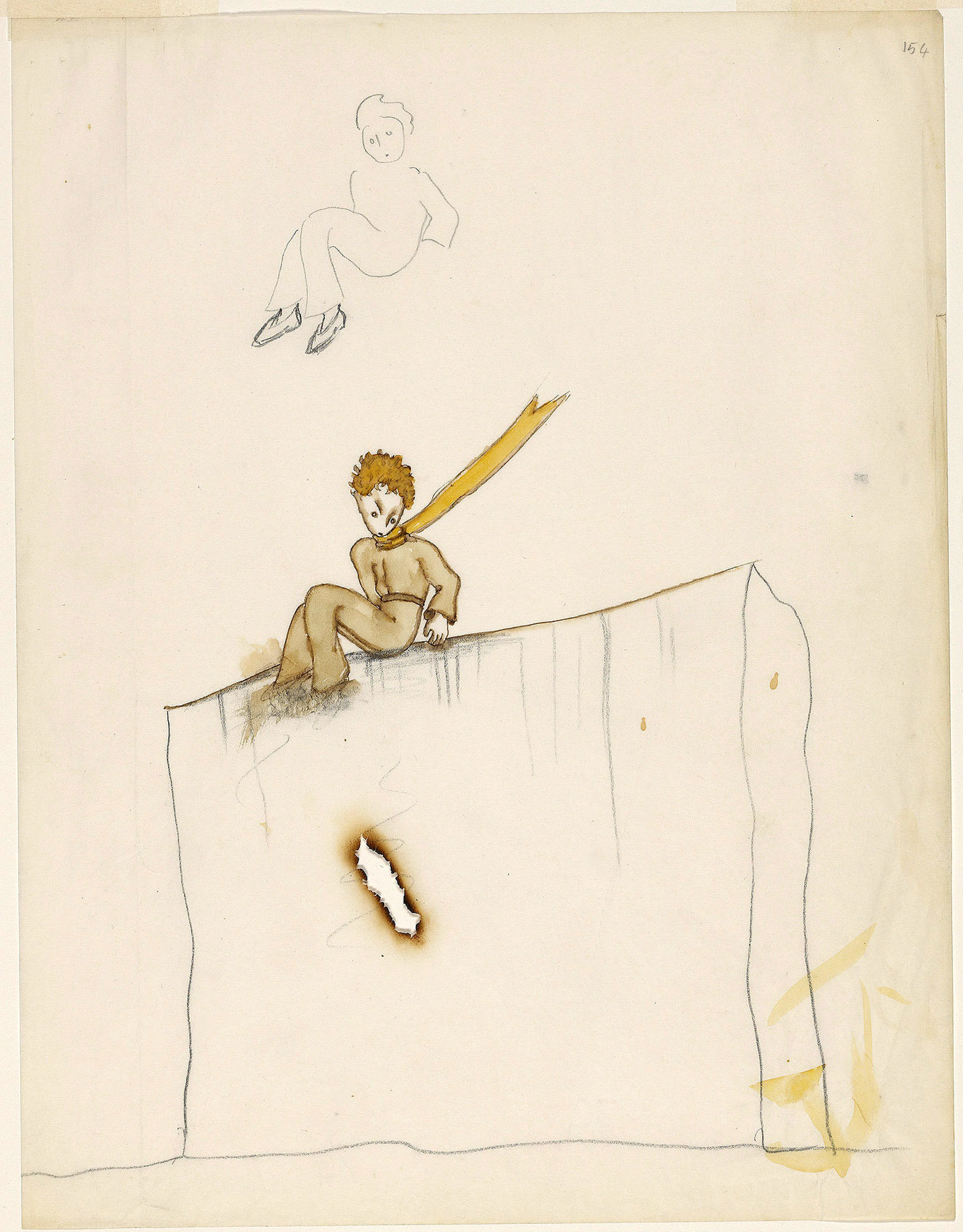

Hamilton (later Reinhardt) nursed Saint-Exupéry through the writing of the book, seeing him nightly for a year. Saint-Exupéry’s biographer, Stacy Schiff, tells us how closely the central figure of the fox was modeled on her. The exhibition relates that when the book was finished, in April 1943, as Saint-Exupéry was rushing off to rejoin his old air force squadron, he “tossed a rumpled paper bag” — a gift — onto Hamilton’s entryway table. It contained the 140 pages of his draft manuscript of “Le Petit Prince,” along with drawings — the heart of what would become the Morgan’s collection.

In “The Little Prince: A New York Story,” the Morgan Library & Museum examines the making of Saint-Exupéry’s classic when he was in exile in New York during World War II.

Credit...Byron Smith for The New York Times Slide 1 of 9

Slide 1 of 9In “The Little Prince: A New York Story,” the Morgan Library & Museum examines the making of Saint-Exupéry’s classic when he was in exile in New York during World War II.

Credit...Byron Smith for The New York Times

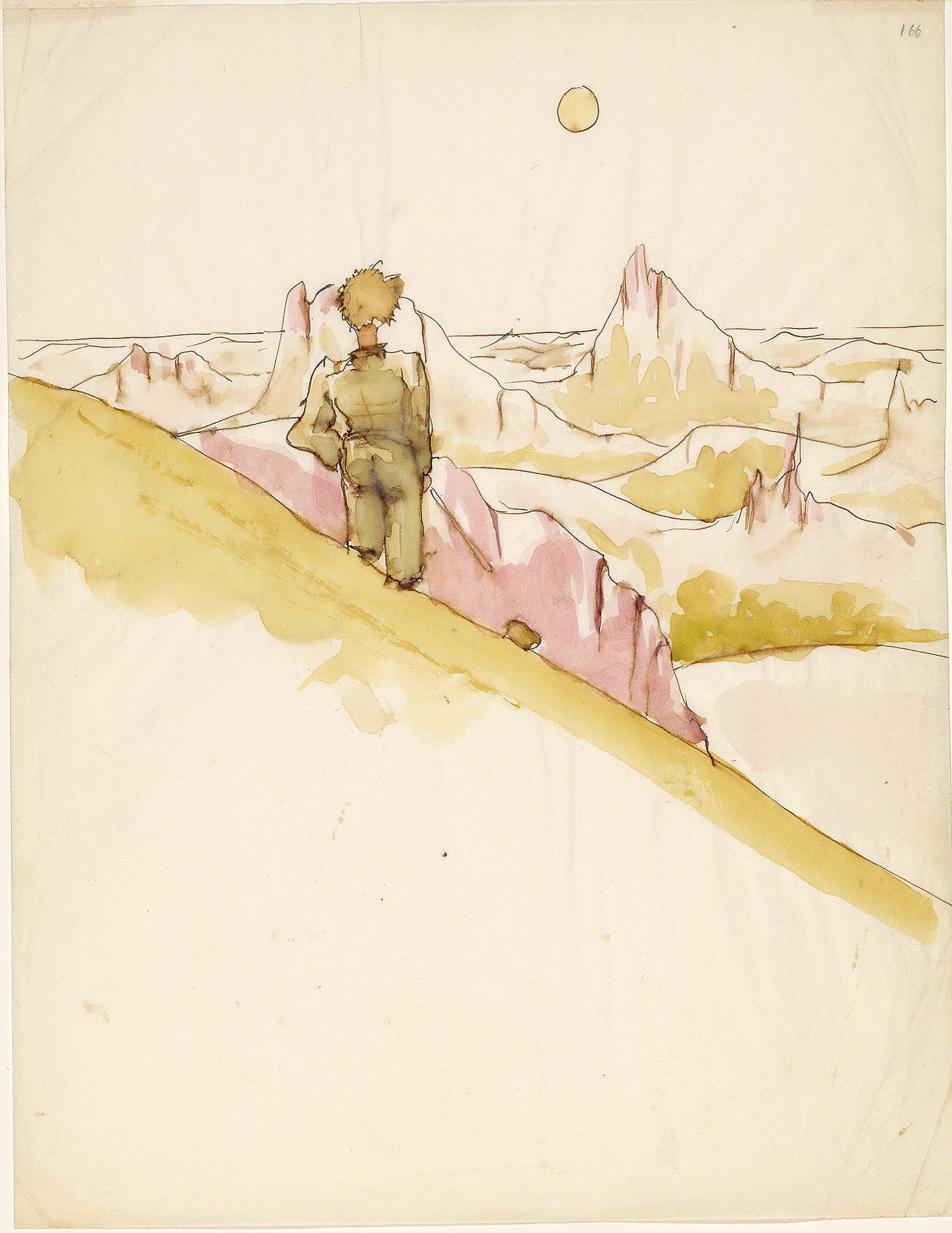

We see 25 of those handwritten manuscript pages (with a watermark reading “Fidelity Onion Skin. Made in U.S.A.”), filled with multiple crossings out and rewordings, which are transcribed and translated in printed gallery guides. These pages form the core of the exhibition along with 43 drawings and watercolors.

The Morgan has displayed some of this material in the past — its last Saint-Exupéry exhibition was 20 years ago, on the 50th anniversary of the book — but not to this extent. And in these pages we see just how much distillation and reorganization took place as he wrote, his manipulations and refinements accompanied by coffee stains and cigarette burns.

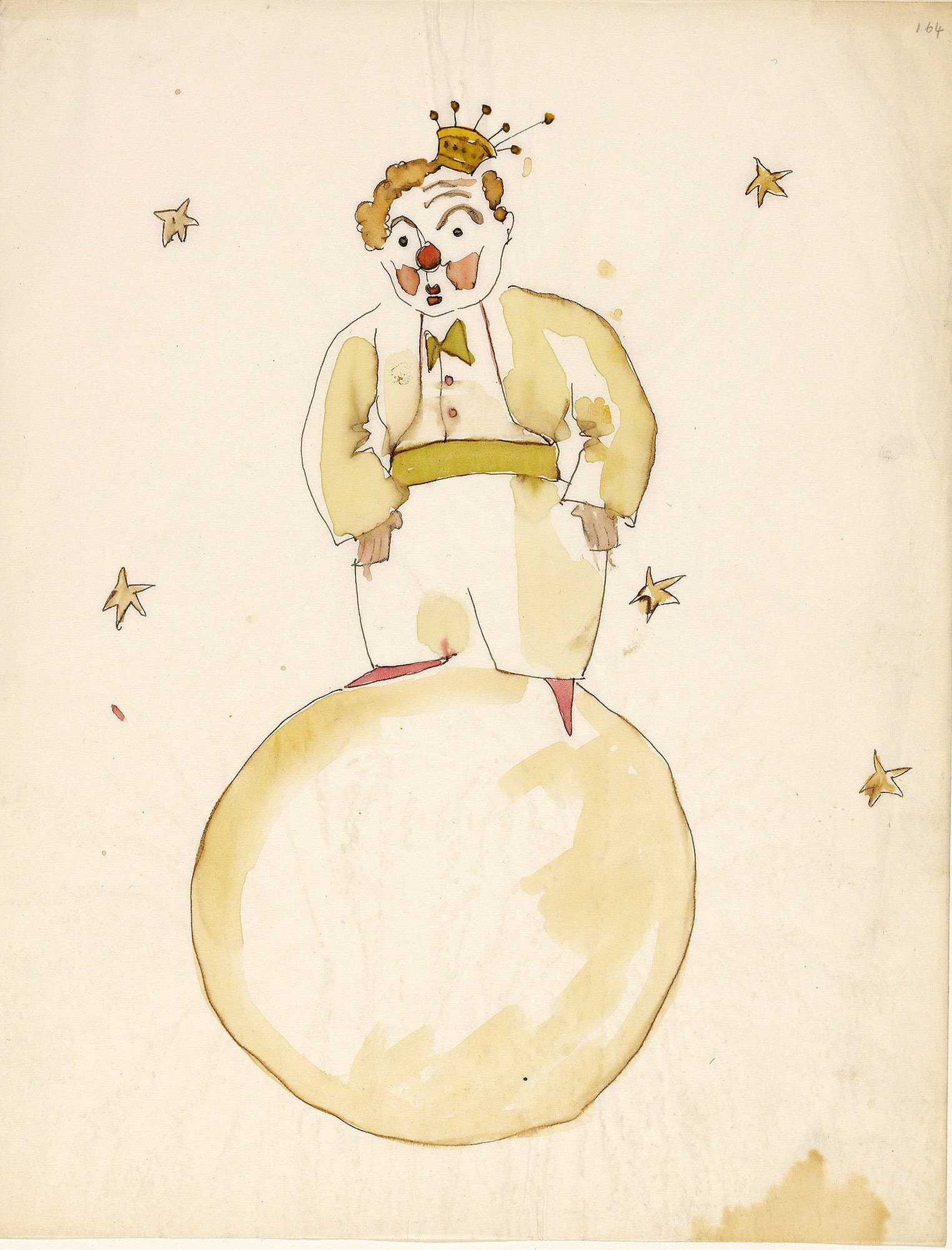

In its completed form, the book is quite different from this penciled draft; it is abstract, fabulistic. The prince describes multiple human types, each inhabiting a miniature asteroid: the businessman who likes to count the stars he thinks he owns, the tippler who drinks out of shame over his drunkenness. “Grown-ups are so strange,” the prince keeps noting.

The narrator — an aviator who crashes in the desert as Saint-Exupéry once did — aspires to the condition of childhood because grown-ups, in his view, can’t really see past the surface of things. The prince has that gift of seeing: He recognizes the asteroid’s types; he even teaches the narrator to see.

In the manuscript pages, though, everything is looser; we see a lot more of the prince’s experiences on Earth, almost all of which are ultimately jettisoned. Rejected passages describe a marketer who champions slogans, hosts who are not hospitable, an inventor of push-buttons that satisfy human desires. Even a grown-up would get the point. Who needs the prince to tell us?

As revisions are made, detail about places is stripped away as well. The author excises mentions of Rockefeller Center and Long Island, leaving us only with numbered asteroids, the Sahara and a Pacific isle. Other cuts are made to keep the crux of the narrative clear: What the prince learns from his encounter with the fox about caring and human connection is also what the narrator will learn from the prince.

Ultimately, in the book, we are left with less about individuals and more about types. It is an aviator’s perspective, sweeping across the landscape, only mildly hampered by earthly ties and human requirements, being guided by the stars. In contrast, the empathetic message of the fox is far more grounded, more concerned with others. Saint-Exupéry may have often been caught between these two perspectives. He fought against detachment but also relished it, fleeing for atmospheric vistas whenever possible.

This may help explain what we learn at the exhibition of his connection with his fellow aviators Anne Morrow Lindbergh and her husband, Charles. Saint-Exupéry spent a weekend at their Long Island home in 1939, and Anne Morrow Lindbergh’s diary entry about reading “The Little Prince” in 1943 is exquisitely compassionate.

But if the author had been more earthbound, less ethereal, would they have become that close? These were, after all, the same Lindberghs who were so enamored of what they had seen of Nazi Germany that they were considering a move to Berlin in 1938. Even in 1941, Charles Lindbergh spoke out crudely against opposing Germany. Yet Saint-Exupéry had originally come to New York to encourage support for France against Germany, and “Le Petit Prince” is deliberately dedicated to a Jewish friend trapped in Vichy.

It sometimes seems as if Saint-Exupéry wants things both ways. During the war years, he tried to map out opposition to Phillipe Pétain, Charles de Gaulle and every other alternative, a position that made him, as Ms. Schiff points out, “calumniated by all.” “Sometimes One Must Judge,” was the title of an essay by Jacques Maritain attacking Saint-Exupéry. A flighty detachment seems to be a flaw in Saint-Exupéry’s temperament, one that “The Little Prince” might be reprovingly trying to correct.

But why let my earthbound analysis have the last word? The exhibition also includes a reference to a rave 1943 review of “Le Petit Prince” in The New York Herald Tribune by P. L. Travers, the author of the Mary Poppins books. She predicts that the book “will shine upon children with a sideways gleam” and “strike them in some place that is not the mind.” Why mourn for the Brothers Grimm, she asks, when it is still possible for such a tale to be “heard from the lips of airmen and all who steer by the stars?”

Advertisement